Since ancient times, one of the most important activities in astronomy was to make maps of the sky, marking down where the stars stood in relation to one another. Making these maps undoubtedly led to the discovery of ‘wandering stars’; the planets of our solar system. Bessel made many sky maps himself which required the precise measurement of the positions of stars in the sky. He would measure the positions of over 50,000 stars in his lifetime. That is a lot of stars!

The gradual improvement in the ability of astronomers to make accurate measurements of star positions eventually led to the measurement of a parallax and the first distance to a star. A first step was the determination in 1718 by Edmund Halley that stars move with respect to each other in the sky.

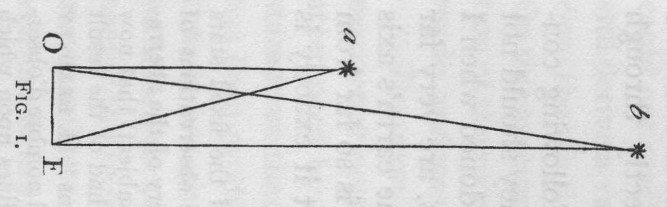

Herschel's General Postulatum of the Parallax: Many astronomers, including Herschel, tried to find the apparent motion of stars (parallax) predicted by the theory that the Earth moves in an orbit around the Sun. Herschel focused on pairs of stars that look very close together, one bright as if it might be close and one faint as if it might be far away. If O and E in the diagram are the positions of the Earth six months apart, the angular measure OaE should be greater than the angle ObE. Some of the pairs Herschel used turned out actually to be at the same distance and to be binary stars of different intrinsic brightnesses orbiting each other. Since he had to look at the stars at different times, he soon realized that the stars were not staying fixed in the sky, but moved back and forth, and thereby discovered binary stars. Image from The Scientific Papers of Sir William Herschel published in London in 1912 by the Royal Society and the Royal Astronomy Society.

Credit: Courtesy The University of Chicago Library

After William Herschel discovered binary star systems in the 1780s, astronomers were able to use Newton’s laws to calculate the mass of stars observed moving in a binary system. The force of gravity tugs on both objects, moving them in ellipses that can be measured. Such a measurement allowed Bessel to find the white dwarf companion to the bright star Sirius.

In 1838, Bessel was the first astronomer to publish a repeatable measurement of a parallax, which is the movement of a star across the background of more distant stars, caused by the Earth in its orbit around the Sun. Measuring parallax allows astronomers to determine distances to nearby stars and intrinsic luminosity.

Each of these three measurements require ever increasing precision in the measurement of the positions of stars.