The Theatrical Baroque: European Plays, Painting and Poetry, 1575-1725

BY | Larry F. Norman

The Age of Theater

All great diversions are dangerous for a christian life, but among all those the world has invented none is to be so feared as that given by theater: it creates a representation so natural and so subtle of human passions that it excites and engenders them in our heart. --Pascal, Pensées, 1655-62  |

Of all the brilliant splendors and alluring vices of baroque France, why would the stern philosopher Pascal dub theater the most dangerous of all social or artistic seductions? The answer is simple: though the period is known for its wildly opulent court festivities, its mania for gambling, and the worldly "gallantry" (as it was then decorously called) of its salons, none of these diversions exercised so forceful a hold on the public as did theater. As Pascal's remark makes clear, the stage captivated audiences with what seemed a perfect reflection of life, an image of human emotions "so natural and so subtle" that it could equal, and even best, the real thing. By the mid-seventeenth century, the theater had allied art and technology to create a medium that vanquished all competitors. Corneille had molded French verse into a perfect dramatic instrument, one that Molière and Racine would soon perfect in their own styles, leaving epic and lyrical poetry well behind in prestige and popular favor. Great advances in stage machinery and design were ushering in a whole new genre of special-effects plays that recreated mythological marvels, miracles and cosmological journeys before captivated audiences. The physical energy, bodily heat, and even sweat and spit of celebrated performers were palpably close to spectators, especially those lucky and wealthy enough to be seated on chairs placed on the stage next to the actors. And thanks largely to some imported talent from Italy, France would soon be experiencing the enchantment of intertwining music and verse as the new form of the opera spread north.

Moreover, as this transalpine influence suggests, there was nothing geographically exceptional about the triumph of theater in France, despite timeless French claims to cultural singularity. In fact, theater obsessed the cultural imagination of Western Europe from the second half of the sixteenth century, when the first permanent theater buildings since antiquity were constructed in Italy; through the Spanish Golden Age; the French classical age; and the English Elizabethan, Jacobean and Restoration periods--in fact through the mid-eighteenth century, when the rise of the novel left the playhouse in an increasingly secondary position in cultural importance.  | |

| Dramatists of the baroque period |  |  | Miguel de Cervantes (1547-1616) Spanish novelist and playwright best known for his novel, Don Quixote.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) English playwright and poet whose major works include King Lear, Macbeth, Hamlet, and Twelfth Night.

Lope de Vega (1562-1635) Spanish poet, playwright and novelist who, along with Calderón, dominated the stage during Spain's Golden Age.

Ben Jonson (1572-1637) English playwright and poet who collaborated with architect Inigo Jones on the production of masques for the Stuart court.

Pedro Calderón de la Barca (1600-81) One of the leading playwrights of Spain's Golden Age, known for his autos sacramentales, one-act religious plays.

Pierre Corneille (1606-84) French dramatist and poet, one of the dominant figures in the evolution of seventeenth-century neoclassical drama.

Jean Baptiste Poquelin Molière (1622-73) French actor-manager and dramatist, one of the theatre's greatest comic artists.

John Dryden (1631-1700) Playwright whose heroic dramas, comedies, and tragedies dominated the English stage during the Restoration period.

Philippe Quinault (1635-88) French dramatist and librettist who collaborated with Lully on a number of large-scale operas.

Jean-Baptiste Lully (1637-82) Italian musician and composer whose career was spent in France, where he dominated musical life for three decades.

Jean Racine (1639-99) The leading tragedian of seventeenth-century France, his plays include Phèdre, Esther, and Athalie. Reproduced with permission from The Cambridge Guide to Theatre, edited by Martin Banham. Copyright (c) Cambridge University Press 1988, 1992, 1995. All Rights Reserved. |  |  |

The period art historians call the baroque was the age of theater. And just as diverse national traditions contributed to this outpouring, so too did various dramatic and poetic genres compete, collide and couple in an explosion of forms. Theater was universal in its ambitions. It represented humanity in historical grandeur, rustic simplicity, urban realism; it depicted gods, saints, and peasants; past kings and present fools. This embarrassment of riches is most famously catalogued (and lampooned) in Hamlet when the verbose Polonius details the traveling troupe's repertoire: "The best actors in the world, either for tragedy, comedy, history, pastoral, pastoral-comic, historical-pastoral, tragical-historical, tragical-comical-historical-pastoral, scene individable, or poem unlimited." These last arcane terms, "scene individable, or poem unlimited," it should be added, signal one last sign of theater's cultural dominance: its hold on the attention of intellectuals and theorists, who spent an enormous amount of energy crafting a learned terminology and a set of abstract principles for the stage. In this case, "scene individable, or poem unlimited" refer to a much debated, and often ignored, rule requiring one single unchanged setting for the entire play, a rule justified by the famous "unities" of place, time and action. These and other elaborate principles were culled, often with great interpolative imagination, from Aristotle's Poetics by late sixteenth-century Italian theoreticians; for the next two centuries they provided fodder for innumerable theoretical prefaces and treatises by playwrights such as Lope de Vega, Corneille, Molière, Jonson and Dryden, as well as for a host of professional theoreticians and critics.

All of this creative activity and theorizing transformed theater into an intellectual and imaginative model for understanding the world in all its aspects. The ancient formula theatrum mundi, the world is a stage, became the motto for the age. Acting and sets, scripts and plot construction were metaphors applicable to every domain of human action: the science of politics, the metaphysics of the universe, the morality of private life--and even the art of painting and sculpting. It is this last aspect that interests us here, and this seminar will explore the most important elements of the dialogue between theater and the visual arts: the relation between dramatic unity and the concentrated storytelling of the canvas, between the actor's art and the rhetoric of gesture in painting and sculpture, between stage design and pictorial construction, and between the role of the theater spectator and that of the artwork's beholder, to name just a few. But before looking at the power of theater to shape both artistic creation and art criticism, let us consider this simple question: Why then? Why did theater exert such a powerful influence over its sister arts in this period stretching from the late Renaissance through the early Enlightenment? The power of the Church, the allure of the palace, the rise of a new elite

One impetus for the rise of theater came from a most unlikely source: the Church. After the Council of Trent (1545-63), the Church launched its powerful propaganda campaign against the Reformation, using all the powers of persuasion at its disposal: opulent architecture and decor, eloquent sermon oratory, powerful painting and sculpture. Despite its continuing distrust of the immorality of theater (actors were, for example, excommunicated), the Church could not easily afford to disdain the persuasive powers of the stage. For the same reasons Pascal denounced theater--its capacity to move the emotions of its spectators with a lifelike replica of human existence--the Jesuits embraced theater as a pedagogical tool. Through a humanistic marriage of the heroic, secular virtues of antiquity and Christian morality, they created images both appealing to a larger public in their human drama and edifying in their intended effect. Dramatic reenactment could, through the power of declamation, gesture, and set machinery, put into living motion the kind of exalted religious images prized in painting and sculpture.  | | The University of Chicago, Smart Museum of Art |  Biblical scenes were popular subjects for painters, as in Noël Hallé's Joseph Accused by Potiphar's Wife. Biblical scenes were popular subjects for painters, as in Noël Hallé's Joseph Accused by Potiphar's Wife. |

Nevertheless, this Counter-Reformation embrace of theater could not everywhere entirely surmount the antagonism between pious devotion and worldly entertainment so powerfully suggested by Pascal. In France, the Jesuit playwright Corneille among others dramatized saints' lives, but these works were highly controversial for their representation of the "mysteries" of Christian faith, felt by many better left to the pulpit alone. Stories from the Old Testament, however, allowed religious passions and edification to enter the stage without the problematic depiction of Christian material. Racine distilled this form of drama to its purest state with his adaptations of Esther and Athalie, condensing the biblical accounts to their barest and most potent theatrical elements. No doubt even more important than the Church in promoting the rise of theater was the political power of princely courts. As feudalism and its attendant dispersion of power died away, new centralized courts sought to increase their sway over the public's imagination with propaganda campaigns that equaled that of the Counter-Reformation Church. And again, nothing advertised their magnificence so well as dramatic spectacles. Presented both outside and indoors, in splendid gardens or palatial halls, court festivities allied the theatrical elements of costumes, sets and stage machinery, and mythological stories with the traditions of jousting games, processions and court balls. The resulting productions not only stunned the original spectators, but were often further publicized through engravings and festival books that illustrated the proceedings.  | | The University of Chicago, Smart Museum of Art |  "Entry of his highness representing the sun," from Jacques Callot's Combat at the Barrier (detail). "Entry of his highness representing the sun," from Jacques Callot's Combat at the Barrier (detail). |

A superb example of this kind of publicizing activity is to be found in a series of prints by Jacques Callot. These engravings were created as illustrations for The Combat at the Barrier (Le Combat à la barrière), an account, in prose and poetry, of the opulent festivities staged by the Duke of Lorraine in 1627 in celebration of the visit of the politically potent Duchess of Chevreuse (Dunbar: see endnotes for references to critical works). All the elements of baroque splendor were employed in this extravagant production: in one engraving alone we find floating fountains, gardens, grottoes and orchestras--all propelled as if by magic by men hidden under the carts--as well as human figures metamorphosed into fruit-bearing trees, and, in a triumphant pose, the fabulously costumed Duke himself as Apollo. The procession of floats and players toured the grand hall of the palace while saluting the hundreds of spectators in the six tiers of seating. The spectacle was occasionally spiced with some theatrical special effects, such as a simulation of exploding heavens and descending planets. This was followed by the chivalric games, which provided a gratifying opportunity for the noble participants/actors to exchange their roles of mythological gods for those of the gallant heroes of Renaissance and baroque romance.

The University of Chicago, Smart Museum of Art | JACQUES CALLOT

French, 1592 - 1635

The Combat at the Barrier, 1627

Engraving and etching This image was part of a set made to record an extravagant spectacle held by the Duke of Lorraine at his court in Nancy. The performance opened with the entry of the participants on elaborate floats. This was followed by a jousting tournament, carefully staged to assure the duke's victory. Callot's prints, together with a description of the spectacle and a transcription of its dialogue, made up a festival book that documented the events. This book was widely collected by the courts of Europe, and had considerable influence on stage design. |

It was of course at Versailles that absolute monarchy created its most spectacular and theatrical expression of power. The formal gardens designed by André Le Nôtre were not only a figurative stage for the court life acted out before the backdrop of the palace; they were also literally a site of the greatest theatrical productions of the period. The grand festivities organized under Louis XIV interlaced fireworks, floats, ballets, and re-enactments of chivalric games with original plays produced on stages harmoniously set in the gardens or courtyards of the palace.  | | The Newberry Library, Chicago |  In addition to hosting the premiere of Tartuffe, the gardens of Versailles provided the stage for Molière's La Princesse d'Elide. In addition to hosting the premiere of Tartuffe, the gardens of Versailles provided the stage for Molière's La Princesse d'Elide. |

Indeed, the great masterpiece of French theater, Tartuffe, was first staged by Molière not on the Paris stage but instead in the luxurious gardens of Versailles, where, after a successful performance, it was immediately banned for the next five years on the charge of suggested impiety. Louis XIV found Tartuffe amusing enough for the enlightened and gallant court, but feared the play's denunciation of religious hypocrisy would be dangerous for the wider public that frequented Paris theaters. The Sun King understood how potent the theater was, and how great an attraction it had for aristocrats and bourgeois alike. It is precisely the theater's new-found fascination for an elite, moneyed and powerful audience that constitutes the final and no doubt most important contributing factor in the triumph of baroque drama. The elaboration of a civilization of manners in Renaissance Italy, exemplified by guidebooks to courtly refinement and culture such as Baldassare Castiglione's Il Cortegiano, spread across Europe as the former feudal and warrior class of the aristocracy was domesticated under centralized monarchies and modern states (Elias). Concurrently, the rising bourgeoisie, often freed from day-to-day business concerns, increasingly mingled with the aristocracy while imitating its manners and decorum. The birth of this new large leisured class created a world in which distinction was no longer political or economic, but instead performative: an accomplished person of quality played his or her role in the social comedy with winning grace and wit. Theater became a metaphor for social role-playing as well as a school where spectators learned to improve their own performance at Town or Court. The growing power of the stage

| | The Art Institute of Chicago |  Laurent de La Hyre's Panthea, Cyrus and Araspus provides a magnificent example of the creative exchange between painting and the stage. Laurent de La Hyre's Panthea, Cyrus and Araspus provides a magnificent example of the creative exchange between painting and the stage. |

The dialogue between painting and theater is as old as the first aesthetic treatises from antiquity. Aristotle compared on several occasions the mimetic properties of painting and theater, paralleling, for example, tragic playwrights with flattering portraitists and comic playwrights with more satirical painters. The exchange between the two arts was strengthened in the Renaissance, though it was still largely painting, sculpture and architecture that dictated their authority to the re-awakening art of drama: sixteenth-century Italian stage designers, for example, learned to apply to theater the rules of perspective derived from the visual arts. However, by the early seventeenth century, theater began to play a more powerful role in this creative exchange, with the delicate balance tipping increasingly in theater's favor. After the mid-seventeenth century, and particularly in France, the growth of academies and the rigidity of neoclassical criticism began to reflexively apply the rules of theater directly to painting, placing the visual arts in submission to dramatic theory. The renowned French painter Nicolas Poussin, for example, was praised at a 1667 session of Louis XIV's Académie de peinture et sculpture for what was described as his finest achievement: painting like a theoretically sound playwright. According to the academic principles of the time, history painting, like tragedy, should condense a story in order to dramatize the essential moment of the "change of fortune" of the hero--in Aristotelian terms, the peripeteia, a passing from happiness to misery or vice versa. Narrative painting was transformed into a freeze-frame of a neo-Aristotelian drama, one designed to produce tragic pathos at a surprising shift in human fate. Noël Hallé's Joseph Accused by Potiphar's Wife illustrates the power of this dramatic model for painting through much of the eighteenth century, and epitomizes in many ways the final celebration of dramatic history painting, a manner that would reach its apotheosis in the early works of David. As the century wore on, theater increasingly lost its centrality in the cultural imagination. The growth of a wider middle-class reading public, often more domestic than worldly, promoted the novel as a conveyer of passions and ideas--and as a means to literary success. Reading in intimacy seemed suddenly more thrilling than sharing the experience of a theater audience. A concurrent new interest in the interior life, exemplified by Rousseau and other pre-Romantic writers, also led to a devaluation of the theater; the passions it once so seductively portrayed on stage began no doubt to appear too public, too conventional, too rhetorical. Of course, new theatrical forms evolved, but by the beginning of the nineteenth century, great writers like Goethe and Musset would create masterworks of theater without any immediate prospects for staging; their audience was found not at the playhouse but in an armchair at home. The power of plays naturally lived on, but the age of theater drew to a close. This session is adapted from Larry F. Norman, "The Theatrical Baroque," in The Theatrical Baroque (Chicago: The David and Alfred Smart Museum/University of Chicago, 2001), 1-11. For a list of the critical works cited in this session, click here.

|

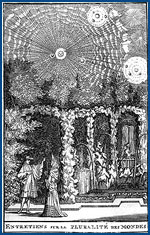

The Art of the Infinite

By the second half of the seventeenth century, most thinkers readily acknowledged what Giordano Bruno had suggested in 1584: that the universe was infinite, containing a multitude of suns around which revolved countless planets. The concept of infinite space generated great excitement and equally great anxiety. In the mid-seventeenth century Blaise Pascal wrote in his Pensées: When I consider the short duration of my life, swallowed up in the eternity before and after, the little space which I fill . . . engulfed in the infinite immensity of spaces of which I am ignorant and which know me not, I am frightened, and am astonished at being here rather than there (Martin, 155).  | | The University of Chicago. Library, Department of Special Collections |  The frontispiece of Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds shows the solar system with the sun at the center and other similar plantetary systems in the distance. The frontispiece of Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds shows the solar system with the sun at the center and other similar plantetary systems in the distance. |

Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle, whose Entretiens sur la pluralité des mondes (Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds) became an overnight sensation in 1686, expressed quite a different attitude. "As for me," says Fontenelle's savant to the Marquise de G., his interlocutor: I feel entirely at ease. When the sky was only a blue vault, with the stars nailed to it, the universe seemed small and narrow to me; I felt oppressed by it. Now that they've given infinitely greater breadth and depth to this vault . . . it seems to me that I breathe more freely, that I'm in a larger atmosphere, and certainly the universe has a greater magnificence (Hargreaves, 63). Fontenelle's words, and Pascal's, remind us of what we appreciate in the great art of the baroque, that combination of exhilaration and foreboding, distinct yet inseparable from one another, which so characterizes the products of the age. The sense of awe peculiar to baroque art resulted from a revolution in the style and manner of representing space. The artists of the seventeenth century inherited from the Renaissance the idea perhaps best expressed by Leonardo da Vinci that "the first object of the painter is to make a flat plane appear as a body in relief and projecting from that plane"; or, in other words, to give the painted object a three-dimensional reality. Baroque artists extended the idea of giving life to the canvas still further. The object was meant not simply to exist in three dimensions but to move. Just as seventeenth-century science introduced motion into our understanding of the physical universe ("E pur si muove" ["But it does move!"] was Galileo's alleged defense before the Vatican council), artists introduced motion into their work, so that space extends into the fourth dimension of time. Baroque art endows the objects it represents with a sense of often extraordinary weight and mass. It conveys a palpable illusion of physical presence. Viewers often notice, for example, the fleshiness of Peter Paul Rubens's nudes or the massiveness of Bernini's famous colonnade at St. Peter's basilica in Rome. The great art critic Heinrich Wölfflin captured another important quality of baroque art in his description of the staircase leading up to the Roman basilica which, he said, "looks like some viscous mass slowly oozing down the slope" (Wölfflin, 45). Baroque art produces an illusion not only of presence but of motion in the sense that a physicist would understand it: the displacement of a body with mass through three-dimensional space over time. In this sense, baroque art is theatrical: the illusion of motion produces an effect that is both figuratively and literally dramatic. The theater, too, is a visual art. At the same time as painters were experimenting with novel effects that suggested movement on canvas, the use of perspectival scenery became common in Europe. Both art forms rely on trompe l'oeil devices, on illusion--tricks of light and the clever placement of drapery, for example--to heighten the viewer's sense of the reality of what is depicted. The space of baroque art is projective. Within the picture, everything recedes toward a vanishing point, plunging into the depths of the pictorial space with exaggerated velocity. The represented objects simultaneously invade the space of the onlooker. Baroque art unites the painting and the viewer in a single space, creating the illusion that the image is as real as its beholder and that the pictorial space extends infinitely. Art historian John Rupert Martin suggests that this sense of pictorial space is analogous to the broader, cosmologic concept of infinity that was gaining hold during the seventeenth century (Martin, 155).

The University of Chicago, Smart Museum of Art | DANIEL GRAN

Austrian, 1694-1757

Design for a Ceiling, circa 1720-57

Pen and black and brown inks with brown and sepia washes and preliminary graphite underdrawing on laid paper The Austrian artist Daniel Gran produced a sense of infinite recession in his stunning Design for a Ceiling, a pen and ink study enhanced with sepia washes. Gran places us below the vault, looking upward past the edge of a fictive dome into a space that seems to have become transparent, open to the sky. A group of figures, one of whom dangles his leg into the space of the building, perches on the edge of the cornice; others, on insectlike wings, hover below. These fantastic figures are able to pass through the frame within the picture, an effect that endows the world depicted on the ceiling with a reality of its own, coextensive with the reality of the space below it. |

Fontenelle suggested a similar breaking down of boundaries in the Entretiens, where he addressed the possibility of visiting the moon, the planets, and the many other worlds that we see suspended above us in the night sky. There, his savant tells the Marquise, we would no doubt find extraterrestrial beings who would seem fantastic to us; we would appear equally strange to them. Gran's winged creatures stare down at us with a mixture of interest and amusement, mirroring our own reaction to their curious appearance. Fontenelle's speculation about the possibility of communication between separate worlds is a common motif of baroque art--equally present in architecture and interior design, as Gran shows us. A wall is never simply a wall, nor a ceiling, a ceiling. Each architectural element is extended beyond its functional duty as a shield from the hostile elements. The aesthetic component of the object, its form, overtakes its function. A wall or a ceiling becomes a possible opening onto the reality which it occludes. A world of light and shadow

--and in baroque art more generally--the effect of movement and action was more important than the effect of symmetry and balance that had dominated the art of the Renaissance. Baroque artists aimed to undo the classical unity of form and function, to unbalance the composition and achieve the impression of movement and space that the new age demanded. In his landmark study Renaissance and Baroque (1888), art critic Heinrich Wölfflin writes: The church interior, [the baroque's] greatest achievement, revealed a completely new conception of space directed towards infinity: form is dissolved in favor of the magic spell of light--the highest manifestation of the painterly. No longer was the aim one of fixed spatial proportions and self-contained spaces with their satisfying relationships between height, breadth and depth. The painterly style thought first of the effects of light: the unfathomableness of a dark depth; the magic of light streaming down from the invisible height of the dome; the transition from dark to light and lighter still are the elements with which it worked. The space of the interior, evenly lit in the Renaissance and conceived as a structurally closed entity, seemed in the baroque to go on indefinitely. The enclosing shell of the building hardly counted: in all directions one's gaze is drawn into infinity. The end of the choir disappears in the gold and glimmer of the towering high altar, in the gleam of the "splendori celesti," while the dark chapels of the nave are hardly recognizable; above, instead of the flat ceiling which had calmly closed off space, loomed a huge barrel-vault. It too seems open: clouds stream down with choirs of angels and all the glory of heaven; our eyes and minds are lost in immeasurable space (Wölfflin, 64-65). Wölfflin discovered the greatest achievement of baroque art at the point where architectural design, with its functional imperatives, met religious art, with its propensity for symbolic statement. In great examples like Bernini's colonnade for St. Peter's basilica in Rome, the two aspects of the baroque--its purely concrete or stylistic qualities, and its idealized purpose--were joined in aesthetic unity, in a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). Contrast is the primary tool through which baroque art prompts a sensation of the infinite in the mind of the beholder. The infinite cannot of course be shown. It must be suggested or implied. What baroque art conveys is an impression, an illusion of infinite space, of movement into boundless depths, by suggesting the existence of what finally remains unseen. Contrast of light and dark, or chiaroscuro, gives space particular qualities. It accentuates the illusion of depth, giving the objects depicted a greater sense of mass and weight while simultaneously heightening their three-dimensionality, making them appear to jump out of the picture frame, or in the case of sculpture or decoration, out of the immediate space that "contains" them. It gives the image dramatic possibilities that steady, even illumination precludes. Like the lighting in films, chiaroscuro in painting works directly upon the spectators' emotions. Curiously, perhaps because the technology was lacking, stage spectacles were slow to adopt the use of dramatic lighting. Other techniques for at once expanding and occluding the pictorial scene in order to create or heighten a mood, such as the use of drapery, found their way into both the visual arts and stage spectacles. It is possible to look at theater in the seventeenth century, particularly its embodiment on the stage, as a branch of the visual arts. The scene was framed and the actors were often described as "painting" their characters. It is less important, however, to draw a direct analogy between the theater and the other visual arts than to suggest that the painter's use of chiaroscuro and the resulting sense of space were---in an important sense--theatrical. The effect of contrast, of drapery, of the deliberate bending and distortion of space was to create a dramatic illusion that suggests the existence of the unseen. Drapery foils the eye's natural curiosity, leading the viewer to imagine that it covers something. The gaze of a figure in a painting who looks off into an unseen space convinces us of the reality of that which we cannot see. Such figures deceive us as certainly and as pleasurably as the actors on a stage convince us of the existence of Hamlet's Denmark or Phèdre's Greece. This is not to say that what is represented has no real reference--Denmark and Greece are clearly real places (although Phèdre and Hamlet are not, at least in our conventional understanding of the matter, real people)--only that the object being represented is not present in the painter's or the actor's depiction of it; that Denmark, in other words, is not really on the stage, or that a figure in a painting is an image, rather than a living being. And yet the success of the depiction depends in some sense on our believing in that being's presence. It hinges upon a painting's ability to get us to believe, not in the reality, but in the presence of what it depicts--the presence, for example, of a three-dimensional body within the surface of the painting, or of the infinite extensibility of the illusory pictorial space--if only in ghostly form. At this, the baroque excels. This session is adapted from Robert S. Huddleston, "Baroque Space and the Art of the Infinite," in The Theatrical Baroque (Chicago: The David and Alfred Smart Museum/University of Chicago, 2001), 13-19. For a list of the critical works cited in this session, click here.

|

Theater of the World

The purpose of playing . . . both at the first and now, was and is,

to hold as't were the mirror up to nature. -- William Shakespeare, Hamlet, act 3, scene 2, lines 20-22 Hamlet's advice to the players offers a philosophy of the theater that was widespread throughout the baroque period, that of art mirroring nature. This philosophy was equally applied by playwrights and visual artists of the time--not surprising, since theater and painting had long been considered sister arts (Lee). But what is the "nature" the baroque artist and dramatist were to mirror? Renaissance scholars had inherited a clear perception of a hierarchical universe from the Middle Ages. According to this view, the world was a perfectly ordered structure, in which God reigns from heaven above, man exists on the earth below, and hell is an underworld lower still. The hierarchical structures of earthly institutions--led by divinely ordained representatives in both the political and religious spheres--mirror this larger, eternal order (Denton). This vision came under assault as the dominance of Catholic theology--which placed man (earth) at the center of God's universe--was challenged both by scientific advances and the Protestant Reformation. In response to these tensions, the Church codified its doctrine at the Council of Trent (1545-63), leading to the establishment of the Counter-Reformation movement. This continuing theological controversy was a manifestation of a general need to restore a sense of harmony and order to the world. Baroque artists operated within this context, creating dynamic works that superimpose concerns about order and disorder upon the traditional representation of hierarchies, both earthly and heavenly. The metaphor of theatrum mundi, or the world as stage, derives from classical sources such as Plato and Horace and from early Christian writers such as Saint Paul (Curtius, 138-44). While not a new concept, it was frequently employed by baroque thinkers to express an ordered world and the forces that threatened it. Throughout Europe, playwrights such as Molière and Shakespeare used the motif in their works to emphasize the close relationship between the stage and life.  | |

| Thinking Points |  |  | - How would you characterize the relationship between the Catholic Church and the theater?

- How did the Church use the stage to support its authority, and how was the theater viewed as a threat by Rome?

|  |  |

Nowhere was this metaphor more pronounced than in Spanish playwright Pedro Calderón de la Barca's 1635 work El gran teatro del mundo (The Great Theater of the World). In this play, Calderón proposed that (to quote William Shakespeare) "all the world's a stage" with God as the ultimate director. As the play opens, the Autor, both director of the play and a characterization of God, uses multiple metaphors to connect the creation of a play to the creation of the world. As actors arrive for their assignments, the Director/Creator gives each one a role that corresponds to a social category (i.e. Beggar, Peasant, King, Rich Man). As the play progresses, the actors must relinquish their earthly roles and pass into the eternal realm. Actors/souls are only allowed into God's presence if they have proven their worth in their roles/lives. Calderón not only reinforced the existence of a temporal or earthly hierarchical order, but he also stressed the ultimate supremacy of the eternal hierarchy found in God's kingdom. There is an illusory quality to the earthly hierarchy, as each man's assigned role in this world is only a shadow of the more permanent part to come. This idea was presented on various stages throughout Europe. Shakespeare employed it (with temporal rather than theological focus) in works such as Hamlet, Macbeth,and most famously, As You Like It: All the world's a stage,

And all the men and women merely players.

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages.

-- act 2, scene 7, lines 138-42 Visual clues and stage machinery

| The University of Chicago,

Smart Museum of Art |  In Pierre Daret de Cazeneuve's title page, heavenly power is directed downward to defeat the enemies of the Church. In Pierre Daret de Cazeneuve's title page, heavenly power is directed downward to defeat the enemies of the Church. |

Seeing an opportunity to reinforce the precepts of the Counter-Reformation, Catholic artists frequently represented the triumph of divine order in the world, employing a well-developed vocabulary of visual devices to do so. These are best seen in Pierre Daret de Cazeneuve's engraved title page (after a painting by Jacques Stella) for the Conciliorum omnium generalium et provincialium, collectio regia (right), a thirty-seven-volume work that describes the proceedings of various councils of the Church (both ecumenical and provincial) from 34 to 1623 CE. This engraving is an allegorical rendering of the Church's struggle against its enemies: a woman, symbolizing Faith or Divine Wisdom, defends herself from the figures--probably emblems of Heresy--who attack her. The power of the Holy Spirit, reflected off a brandished shield, allows her to repel these forces. A fragmentary view of a statue of Saint Peter, whose keys to the gates of heaven point directly down at the papal tiara, signals the source of the pope's authority and the channels of divinely controlled hierarchy.

As this image makes clear, composition is crucial in baroque depictions of hierarchy and theatrum mundi. The spatial arrangement of stage or canvas could demonstrate a naturally ordered universe through the manipulation of vertical and horizontal positioning. In response to new imperatives, theatrical space evolved from the bare medieval stage to an elaborate Italianate one, characterized by machinery, large sets, and spectacle. Playwrights across Europe used a vertical visual hierarchy: stage architecture, reflecting the architecture of the world, placed the heavens above and the underworld below. The highest spaces (balconies, platforms, the increasingly important "flying" machinery) denoted the province of kings, gods, and other lofty characters. For example, in The Tempest's wedding masque, the goddesses most likely appeared on the balcony while the sub-human Caliban inhabited the hellish world of the understage space, accessible through trapdoors. A similar vertical hierarchy is evident in many of the objects considered in this seminar. For example, in Pierre Daret de Cazeneuve's engraved title page to the Concilium omnium generalium et provincialium, collectio regia, chains of command clearly flow from the top to the bottom of the work. The literal and figurative "highest" level contains both the statue of Saint Peter and the dove that represents the Holy Spirit. In the earthly realm directly below, the papal tiara represents the temporal version of Saint Peter's eternal ecclesiastical power. Interestingly, Faith pushes her enemies not only out of the frame of the picture, but also downward, toward hell. The lowest figure in the work, in fact, is a vanquished foe who has fallen to the ground and whose body disappears into darkness--all we can see of him is his left leg.

While verticality may seem to be a natural means of expressing hierarchy, the horizontal axis can also establish such an ordered structure. Calderón's El gran teatro del mundo exemplified horizontality on a baroque stage. The play has its origins in medieval autos sacramentales, religious dramas performed by traveling troupes around two carts. In the sixteenth century, emerging Spanish drama had moved into corrales, open-air theaters similar in design to Shakespeare's Globe Theatre. Religious drama followed suit, as playwrights took advantage of the new stage space. Calderón's autos featured stylized carts placed on the stage itself. The result was a space that encouraged playwrights to compare, left against right, two places or events. In El gran teatro del mundo, the two carts represent the earthly and heavenly reigns, creating a literal, theocentric theatrum mundi. Francesco Fontebasso's painting The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine (below) also emphasizes a horizontal juxtaposition. The emperor, at the right, theatrically stretches his arm to guide the viewer's gaze horizontally across the painting to Catherine's impending execution. At that point the vertical axis comes into play, as light from above bathes the central figure. Catherine, at the moment of her martyrdom, thus represents the conjunction of the horizontal and vertical hierarchies and encourages a comparison between the earthly and divine orders.

The University of Chicago, Smart Museum of Art | FRANCESCO FONTEBASSO

Italian, 1709-69

The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine, 1744

Oil on canvas Fontebasso presents Saint Catherine's martyrdom as a sort of baroque spectacle. By placing the saint on a raised platform he recalls open-air stagings, while his depiction of a heavenly chorus suggests a deus ex machina, a great theatrical apparatus descending from the upper reaches of the stage. Like the baroque device of the play-within-a-play, the inclusion of an audience in the picture is a characteristic way of calling attention to the act of viewing and to the artifice of a work that, at the same time, is trying to convince us of its reality. |

Fontebasso created a frame for this scene by arranging various figures around his heroine, Catherine, who occupies the middle ground. In a similar vein, discovery spaces that opened off the rear wall of the baroque stage could be used to disclose important events or characters, even though they were located farther away from the audience. For example, at the end of The Tempest, Prospero reveals the blissfully united Ferdinand and Miranda in the discovery space. Discovery spaces remind us that the baroque stage was open and expansive: dialogue was spoken from offstage, characters could enter or exit through trapdoors or from trapezes, and the discovery space added depth and dimension to the main stage area.  | | The Art Institute of Chicago |  Laurent de La Hyre's Panthea, Cyrus, and Araspus. Laurent de La Hyre's Panthea, Cyrus, and Araspus. |

In France where, in accordance with the rules of decorum, violent acts could not be shown on stage, the offstage space was particularly important. Pivotal events would be reported to the audience via a messenger character. Visually, the doorway in Laurent de La Hyre's Panthea, Cyrus, and Araspus (right) functions as a discovery space, by opening up the back wall and revealing a large massed army to the painting's audience. Both baroque painting and staging created tight dramatic spaces that opened up to accomodate sophisticated narrative structures; in the story presented by de La Hyre, the fate of the armies in the distance will largely determine the fortunes of the characters who occupy the foreground. For the baroque artist, the world truly was a stage, reflecting the ever-present tensions of a changing world. Counter-Reformation theologians, challenged by new religious and scientific theories, strove to reestablish traditional perceptions of an ordered world. These ongoing controversies shaped the baroque view of the universe, paradoxically typified by both tension and order. Baroque artists and playwrights rose to the occasion with boundless energy and explosive creativity, questioning and redefining the relationship between art and life. This session is adapted from Anita M. Hagerman-Young and Kerry Wilks, "The Theater of the World: Staging Baroque Hierarchies," in The Theatrical Baroque (Chicago: The David and Alfred Smart Museum/University of Chicago, 2001), 36-45. For a list of the critical works cited in this session, click here.

|

Social Performance

| In an argument that was to inflect for centuries discussions of genre and representation, Aristotle claimed that one could distinguish between different genres based on their approaches to the depiction of human individuals. According to his Poetics, art could represent men better than they are, worse than they are, or just as they are (Norman, et al.). Traditionally, tragedy sought to depict individuals as better than they are, while comedy trafficked in the portrayal of individuals as worse than they are. Most significantly, even in Aristotle's own original formulation, the third mode--in which artistic representation does not meaningfully depart or diverge from its object--never receives fuller qualification. This third mode remains an unfilled slot in the Poetics, and a possibility that medieval and Renaissance commentators left largely undiscussed. fundamental departures from previous aesthetic debate, however, consisted in a sustained and anxious scrutiny of this empty slot. More precisely, baroque commentators considered not only how one might depict men just as they are, but what the stakes involved in such a move might be. Critical voices in the seventeenth century came to see these stakes as consequential indeed, concerning no less than the purpose and character of artistic portrayal, and the question haunted much of baroque aesthetic debate. Much of the heat surrounding this debate proceeded from the opening of a novel gulf in seventeenth-century thought: the traditional privileges of art were set against the humbler work of accurate portrayal. Artistic imagination could either have free reign, the capacity to idealize and beautify the model in reference to an intellectual type, or it could restrain itself, aiming to do no more than render the true, understood to be what was visually present. Partisans of the first approach attacked practitioners of the second as mere copyists, while these artists in turn derided their critics as unskilled draftsmen, ill prepared for the challenges of duplicating nature (Félibien, et al.). Whether portraits appeared in theatrical or pictorial form, all were subject to this dispute. The work of the satirist Molière provides especially telling examples in this context, since it became something of a commonplace in baroque discussion that his comic plays were fundamentally a series of portraits, copied and stitched together directly from life, without the mediation of artistic selection and control. The following excerpt about Molière from Jean Donneau de Visé's 1663 play Zélinde underscores the intersection of drama and painting when it comes to such pillaging and copying. The characters Argimont and Oriane explicitly address the matter, describing Molière's compositional method as follows: Argimont: [Molière] had his eyes glued to three or four people of quality. . . . He appeared attentive to their discourse and it seemed that, by a movement of his eyes, he looked right into the bottom of their souls in order to see what they were saying. I even believe that he had some tablets and that, with the help of his coat, he wrote, without being seen, all the most remarkable things they said. Oriane: Maybe it was a crayon, and he drew their expressions in order to represent them naturally on stage. Argimont: If he did not draw them on the tablets, I don't doubt that he printed them in his imagination. He is a dangerous person (Donneau de Visé, 37-38). Molière's actual working method probably bore little resemblance to the procedure that Donneau de Visé delineated, but what matters at present is the implication that Molière's work--as a species of comedic portraiture that allegedly goes so far as fully to copy the appearance and actual conversations of those it satirizes--represents an art form that duplicates rather than amplifies its subjects. The art of representation

| | The National Gallery of Art, Washington |  Anthony Van Dyck's portrait places the young Lord Wharton in the midst of a pastoral fantasy. Anthony Van Dyck's portrait places the young Lord Wharton in the midst of a pastoral fantasy. |

Anthony Van Dyck's Philip, Lord Wharton, for example, strives to do more than copy the visual aspect of its subject. While it is too much to say that the portrait presents Lord Wharton as necessarily better than he is, it does deploy the trappings of Arcadian and pastoral simplicity to assimilate him to a flattering type of humanity, quite possibly the contemporary ideal of the honnête homme. The seventeenth-century notion of honnêteté has two dimensions, both of which are relevant to the present discussion. On the one hand, it denotes ease, directness and a lack of affectation in manner. This species of man had no apparent recourse to artifice or self-composition in his bearing or social interaction, but carried himself in a way that was the perfect picture of the genuine, casual and unpretentious. Such an individual embellished himself and his conversation just enough to be engaging, but never so much as to seem precious or affected. Certainly, Van Dyck's decision to insert his wealthy patron into a rustic environ derived from a desire to treat Lord Wharton as an example of such a flattering type. On the other hand, one needs to bear in mind that this perfect picture of the genuine and direct was precisely that, a "picture." That is, the baroque age tended to conceive the individual, above all in social interaction, as a construct, or product of art, whose image in the eyes of others was subject to manipulation and composition. The honnête homme distinguished himself from his peers not by the absence of art in his carriage and aspect, but by making it exceptionally difficult for observers to catch that art. In a way that parallels certain tenets of baroque aesthetic theory, the individual in social interaction was never to reveal the constructive means he deployed to make his image. The standard to which the artwork and the social being ultimately aspired was largely the same: an artfulness that did not reveal itself in too overt a fashion. Although Van Dyck did not openly proclaim that Lord Wharton practiced such an artfulness (that would ruin its effect), one might usefully think of the sitter in this portrait as an embodiment of perfect construction and seeming casualness, the very type of honnêteté.  | | The University of Chicago, Smart Museum of Art |  Franz Anton Maulbertsch's The Sausage Woman reflects the artist's efforts to depict the world as it was, rather than to idealize his subjects. Franz Anton Maulbertsch's The Sausage Woman reflects the artist's efforts to depict the world as it was, rather than to idealize his subjects. |

Franz Anton Maulbertsch's work exemplifies a very different aesthetic approach. In The Sausage Woman (left), Maulbertsch did not attempt to show, by incisive departures from surface appearances, the essence of these fairly humble individuals. He held himself to the humbler goal of trying to produce a visual record. He primarily attempted to duplicate the sort of scenes and views with which his audience would already have been familiar, because they were the scenes and views that comprised the audience's life. As though taking a species of visual dictation, Maulbertsch tried to amass observations and details taken directly from the world about him. At times, the pleasures of duplication go so far as to permit the audience to participate in its own depiction. The work of Molière represents the finest theatrical specimen of this scenario. Donneau de Visé's description of Molière's working method again provides a key. Not only did Molière secretly copy down the words and physical appearance of those he met in society; these people--who would comprise the eventual audience of his plays--actually sent him material in the form of dialogues and incidents from their own lives that Molière proceeded to incorporate into his own work: All those who give him memoires want to see if he uses them well; some go there [to his plays] for half a verse, others for a word, others for a thought which they pray him to use. . . . This justly makes one believe that the great number of self-interested theatergoers who go to these plays is what makes them succeed (Donneau de Visé in Molière, 1020). According to this argument, Molière's satires flourished from receiving "accounts of all that was happening in society, and portraits of their [the audience's] own faults, and those of their best friends, believing that they would be glorified by having their impertinences recognized in his works" (Donneau de Visé in Molière, 1019). Molière's work represented the pinnacle of portraits that were radically non-amplifying in their descriptive endeavor. Within the context of baroque discussion, Molière's status as copyist was such that he let the subject he chronicled and depicted, the audience and its social world, literally author itself. Although Molière, with his hidden pen and paper, certainly added observations of his own to his plays, one finds little indication in baroque discussions of the author that his depictions diverged on any essential level from the models he observed in society. Molière's satiric works thus amounted, in the mind of much of his public, to a generic transcript of social perception and derision.  | |

| The appearance of emotion |  |  | Correspondence between a mother and daughter provides evidence of the theatricality--and the self-consciousness of the actors--that characterized the baroque period. In a letter to her daughter dated May 21, 1676, Madame de Sévigné described the real-life performance of one Madame de Brissac: Mme de Brissac had colic today. She was in bed, beautiful and bonneted in the most sumptuous fashion. I wish you could have seen what she made of her pains, and the use of her eyes, and the cries, and the arms, and the hands which trailed over her bed-clothes, and the poses, and the compassion which she wanted us to have. Overcome with tenderness and admiration, I admired this performance and I found it so beautiful that my close attentiveness must have appeared like deep emotion which I think will be much appreciated. (Hammond, 115) |  |  |

What made this most radical kind of duplication possible was the baroque conception of social life and social interaction. As we have seen in the case of the honnête homme, an individual's self-presentation was constantly subject to judgment by others. If an individual was seen to carry and compose himself badly, if he was clumsy in the art of self-presentation and self-construction, he became a potential target for derision and mockery. The stakes at play in such social evaluations were enormous; since the individual's position was conceived in relation to others, his very identity was on the line. These standards largely converged with the standards that were brought to bear in the evaluation of a work of art. A striking passage from the work of the seventeenth-century essayist Pierre Nicole throws light on this idea: Man does not form his own portrait on what he knows about himself through himself, but also by seeing the portraits that he discovers in the minds of others. Because we are to one another like the man who serves as a model in the Academy of Painting. Each of those who surrounds us creates a portrait of us. . . . But what is most significant in this is that men do not simply make the portraits of others but that they can also see the portraits that one makes of them (Nicole, 3:16). In Nicole's conception, an individual in the social world is a wanderer among a crowd of portraitists--portraitists whose work will help determine that individual's understanding of himself. Perhaps because so much depended on one's ability to make the right impression on others, baroque social existence came to resemble an unending duel of rival portraitists. One never escaped the viciously discerning gaze of others, nor the cutting remarks or savage depictions they might engender. It is not too much to describe this social world as the endless circulation of warring satires. This session is adapted from Josh Ellenbogen, "Representational Theory and the Staging of Social Performance," in The Theatrical Baroque (Chicago: The David and Alfred Smart Museum/University of Chicago, 2001), 21-31. For a list of the critical works cited in this session, click here. |

SESSION 5: The Art of Fragile Harmony

| The pastoral genre that triumphed in baroque theater and art claimed a long and noble genealogy. Though it was born in Ancient Greece with Theocritus' Idylls (third century BCE), it is the Vergilian model of the pastoral (first century BCE) that most influenced writers and painters of the Renaissance and baroque periods. Vergil set his eclogues in Arcadia, which became the idealistic locus amoenus (pleasant place) where shepherds could poeticize freely, away from the vicissitudes of urban life; they could live in otium (leisurely), entirely devoted to poetic creation and musical expression. The Renaissance took on this literary model and developed it further; Italy in particular produced some major pastoral works that would have a tremendous impact on the formation of the baroque pastoral, and it introduced pastorals to the theatrical stage (Freedman, et al.). During the baroque age, the pastoral genre evolved in harmony with new literary and pictorial aesthetics. Focusing primarily on France between 1650 and 1700, we will explore the close links between two domains: pastoral theater and pastoral painting. We will see that theater and painting share the same aesthetic rules, according to which the internal dynamics of the work are based on the tension between the harmony of nature and the disruptions of dramatic conflict; and we will explore how pastoral landscape eluded the boundaries between illusion and reality, between the fictional fields of the shepherds and the very real gardens of Versailles. From its classical beginnings, the pastoral genre was associated with the stilus humilis (simple style); its standard format is the eclogue, a short dialogue between two shepherds extolling the beauties of nature. Pastoral poets had neither the intention nor the means to compete with higher genres such as the tragedy or the epic. There was no doubt among critics at the time that pastoral evocations must be plain, simple representations of a pliant, gentle nature. This simplicity, however, is not easy to achieve; as a result, pastoral settings are paradoxically complex. Harmony and conflict

Many baroque works of art, both literary and pictorial, portray an environment in essential but fragile harmony, with the threat of disruption never very far away (Panofsky, 17-88). This question of harmony is linked to the concept of les bienséances (decorum), which was central to the social life and thought of the seventeenth century. The pastoral had to give pleasure through a depiction of shepherd life that was simple and natural without being vulgar. The famous French critic and poet Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle had criticized both ancient Greek and more recent French poets for creating shepherds that were either too close to the real thing, or that spoke of life in such philosophical tones that verisimilitude was lost. For him, the challenge in poetry was to find a delicate balance between refinement and rusticity, for an excess of one or the other was improbable or unpleasant. The search for this simple harmony was also problematic for the pastoral landscape painter. The great art critic and theorist Roger de Piles was less concerned with the physical features of shepherds than with their activities; he stressed the necessity of avoiding potentially static inaction, and maintaining the interest of beholders. In literary pastorals, the action is extremely reduced and revolves around love and poetical creation. In paintings, some features stemming from this convention are noticeable--shepherds playing lutes, pipes, or pan flutes, or nymphs frolicking with satyrs--but the problem remains of exciting the viewer's interest in these conventional pastoral diversions. De Piles wrote in 1709: I am persuaded that the best way to make figures valuable is, to make them so to agree with the character of the landskip [sic], that it may seem to have been made purely for the figures. I would not have them either insipid or indifferent, but to represent some little subject to awaken the spectator's attention, or else to give the picture a name of distinction among the curious (de Piles, 140).  | | The University of Chicago, Smart Museum of Art |  Claude Lorrain's Apollo Leading the Four Seasons. Claude Lorrain's Apollo Leading the Four Seasons. |

It was a challenge for the pastoral landscape painter to represent a locus amoenus as a setting for action; it had to be peaceful and yet somehow stimulating to the beholder. Even when harmony is achieved, the threat of disruption is never far. In pastoral theater, harmony can be disrupted by death, rapture, or loss of love; these themes are also present in pictorial representations of pastoral landscapes. Many baroque painters made use of the allegorical possibilities of pastoral landscape, most notably Claude Lorrain (Unglaub, 46-47). A closer look at Claude's Apollo Leading the Four Seasons (left) demonstrates the tenuous equilibrium on which the pastoral representation is built. Illusion and reality

| The University of Chicago. Library,

Department of Special Collections | | Like many productions of the baroque period, the opera Atys drew upon classical mythology. |

This dialectic between harmony and disruption, which seems to underlie most baroque landscapes, provides the pastoral with its dramatic narrative force. But another tension, that between illusion and reality, makes the pastoral a uniquely theatrical form. While some literary genres of the seventeenth century, such as tragedy, relied heavily on the notion of verisimilitude and had to give the appearance of reality, pastoral aesthetics permitted obviously artificial devices on stage. For example, pastorals often include the intervention of a deus ex machina (literally, god from a machine). French baroque opera, which derived from the lyric pastoral of Pierre Perrin and its offspring the lyric tragedy, frequently featured magic, druids and pagan deities on the stage (Kintzler). In Atys, a lyric tragedy by Philippe Quinault and Jean-Baptiste Lully, several key moments in the action rely on supernatural interventions. In one instance, the goddess Cybele, jealous of Atys's love for a mortal woman, nearly drives him to suicide; in the end, she takes pity and changes him into a pine tree. Many pastoral dramas and paintings depict magic, gods and monsters in a variety of contexts. Classical mythology was a favorite source; a more recent inspiration was Ludovico Ariosto's Orlando Furioso (1552), a chivalric romance set in Charlemagne's time. Cecco Bravo's painting Angelica and Ruggiero (below) depicts an episode from cantos X and XI: Angelica, princess of Cathay, is saved by the paladin Ruggiero from the monstrous Orca. Ruggiero leaves his winged steed (shown flying away in the background) and hastens toward the princess to claim his reward of a thousand kisses. Cecco Bravo depicts the moment just before Angelica, by means of a magic ring, disappears into thin air, leaving Ruggiero behind.

The University of Chicago, Smart Museum of Art | FRANCESCO MONTELATICI, called CECCO BRAVO

Italian, 1607-61

Angelica and Ruggiero, circa 1640-45

Oil on canvas The story depicted in this canvas comes from Ludovico Ariosto's Orlando Furioso (1552), a favorite literary source for baroque spectacles. Here, the princess Angelica is about to escape her suitor Ruggiero, using the powers of a magic ring to make herself disappear. Illusionism was an important element of pastoral productions, which often made use of a deus ex machina. Literally a "god out of a machine," this invention permitted the staging of supernatural events, and satisfied the audience's demand for breathtaking theatrics. |

The supernatural charms of Ariosto's world later provided a rich resource for theatrical spectacles, and we will return to one such example at Versailles momentarily. But the magical elements are only one of the most obvious ways pastorals play with the notion of illusion. In Theocritus's Idylls and Vergil's Eclogues, gods very often appear disguised as shepherds, but beginning in the Renaissance and intensifying during the baroque period, aristocrats appropriated this disguise. Indeed, the mask is of particular importance in the baroque period; in a society where the social gaze imposed a powerful pressure on the public persona, masks represented escape from scrutiny and a way of presenting oneself in a carefully constructed, highly artful guise. Very often aristocrats would play the role of shepherds, retiring to their locus amoenus and allowing themselves to compose poems and play music.  |  National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Collection National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Collection |

It is not surprising to see the arts of portrait and pastoral painting merge, as is the case in Anthony Van Dyck's portrait of Philip, Lord Wharton (left). Van Dyck portrayed Wharton as an elegant shepherd, with cape and crook, in front of a landscape. While a very subtle palette of tones seems to place the figure in perfect harmony with the background, a drape, hanging quite strangely from the top of the painting, separates the foreground and background, clearly revealing that the subject is only playing a role. An even more complex means of revealing and deepening the illusion of representation is found in the widespread baroque strategy of constructing a mise en abyme, or a mirror effect. In the visual arts, this generally took the form of an image within an image; courtly spectacles often featured a play-within-a-play. Because pastoral references figured so prominently in courtly role-playing and self-fashioning, pastoral productions intensified this kind of self-reflexivity, constructing often dizzying relationships between reality and performance.  | | The Newberry Library, Chicago |  A performance of Molière's La Princesse d'Elide in the gardens of Versailles, from the Plaisirs de l'isle enchantée. A performance of Molière's La Princesse d'Elide in the gardens of Versailles, from the Plaisirs de l'isle enchantée. |

Molière's 1663 Princesse d'Elide is exemplary here in its intricate game of illusions. The play was part of the Plaisirs de l'îsle enchantée (Pleasures of the Enchanted Isle), a three-day celebration that inaugurated the new palace of Versailles and that was set in the sumptuous gardens designed by André Le Nôtre. The theme of the spectacle was adapted from the ever-popular Orlando Furioso. Louis XIV himself appeared in the role of chevalier Roger and leading courtiers took on other roles. In one episode (in which Molière played Lycidias), Roger and the knights, held prisoners on an enchanted island, are allowed to present a play to pass the time--this play-within-a-play is La Princesse d'Elide. It is hard to know if the audience at Versailles identified Louis as the king or as Roger, and whether they interpreted the performance as a production directed at Roger's fictional retinue or as a modern entertainment created for the French court. The play within the play being watched by Roger/Louis XIV complicates the illusion further by presenting numerous pastoral interludes. In a dizzying triumph of theatrical showmanship, the pastoral scenes on stage mirrored perfectly the garden setting of the audience. And just as Molière's interludes featuring satyrs, singing echoes and bucolic dances play ironically with the artificiality of pastoral conventions, so too Le Nôtre's formal gardens self-consciously mixed mythological statuary and heroic grandeur with the simple charms of nature. Thus the fictional stage world echoed the audience space in both pastoral simplicity and elaborate artifice. This was a breathtaking reconciliation of the tension between nature and artifice, but one entirely typical of an age that considered the enjoyment of pastoral simplicity an occasion for spectacular theatrical invention. This session is adapted from Véronique Sigu, "The Baroque Pastoral or the Art of Fragile Harmony," in The Theatrical Baroque (Chicago: The David and Alfred Smart Museum/University of Chicago, 2001), 58-67. For a list of the critical works cited in this session, click here. |

ABOUT THE AUTHORLarry F. Norman

Larry F. Norman is assistant professor in the department of Romance languages and literatures at the University of Chicago. The Theatrical Baroque developed out of a graduate seminar he taught on this subject in 1999. A specialist in seventeenth-century French theater, Professor Norman is the author of The Public Mirror: Molière and the Social Commerce of Depiction (University of Chicago Press, 1999).Elizabeth Rodini

Elizabeth Rodini is the Mellon Projects Curator at the David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art. Other exhibitions curated in collaboration with University of Chicago faculty include The Place of the Antique in Early Modern Europe, Pious Journeys: Christian Devotional Art and Practice in the Later Middle Ages and Renaissance, and A Well-Fashioned Image: Clothing and Costume in European Art, 1500–1850 (opening at the Smart Museum October 23, 2001).

The Theatrical Baroque was made possible by a grant to the Smart Museum from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to encourage innovative uses of the museum’s collection by University of Chicago faculty and students. Each Mellon project consists of three principal components: an exhibition, a fully illustrated exhibition catalogue authored by faculty and students, and a course taught by the participating faculty member. Upcoming Mellon projects and their faculty curators include A Well-Fashioned Image: Clothing and Costume in European Art, 1500–1850 (Professor Elissa B. Weaver, October 23, 2001–April 28, 2002); Confronting Identity in German Art, 1800–2000, (Professor Reinhold Heller, fall 2002); and Enchanting Images: Picturing Narratives in Renaissance Art (Professor Frederick De Armas, spring and summer, 2003).

With Contributions by:

Josh Ellenbogen, Anita M. Hagerman-Young, Robert S. Huddleston, Véronique Sigu, and Kerry Wilks

COPYRIGHT

Copyright 2001 The University of Chicago. For a complete list of the works shown in this seminar, click here.