The

king, Osiris, and the rituals of rejuvination

One of the most significant functions of Egyptian

ritual and myth was the reinforcement and protection of the office

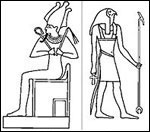

and body of the king. The most important myth associated the entity

of the king with the gods Osiris and Horus. According to the myth,

Osiris, the first king of Egypt, was murdered by his evil brother

Seth. His death was avenged by Horus, the son of Osiris, and mourned

by his sister/wife Isis and her sister Nephthys. This basic outline

has myriad variations, the most elaborate version of which appears

in the second century AD writings of Plutarch, but the focus of

the myth was to associate the living king with the god Horus and

his deceased predecessor with his mummiform father Osiris. In this

way, each king of Egypt was incorporated into a mythological descent

from the time of the gods. The myth also stressed filial piety and

obligations of a son to his father. Osiris (or, according to various

versions of the myth, at least part of the god's body) was thought

to have been buried at Abydos, accounting for the sacred nature

of the site throughout Egyptian history.

By the late Old Kingdom, posthumous identification with the god Osiris

was adopted by the common people. After death, if they had lived their lives

according to Maat and could truthfully confess that they had not committed

any mortal sin before the divine judges in the Hall of Two Truths, they

were admitted into the company of the gods. Coffins and funerary objects

of the New Kingdom record that the name of the deceased was compounded with

that of the god, and that the face of coffins belonging to men bore the

false beard of Osiris.

Many rituals were dedicated to the eternal rejuvenation of the

living king. The most important was the Sed festival (also known

as the "jubilee"), which is attested from the Early

Dynastic Period and was celebrated up to the Ptolemaic era. Throughout

most of Egyptian history, the ritual was celebrated on the thirtieth

anniversary of the king's accession to the throne and thereafter

at three-year intervals. During the course of the festival, the

king alternately donned the red crown of Lower Egypt and the white

crown of Upper Egypt and, grasping implements such as a slender

vase, a carpenter's square, and an oar, ran a circuit between

two B-shaped platforms. The king was then symbolically enthroned.

Because the central act of the ritual — running the circuit

— was physical, the Sed festival may be the vestige of a

Predynastic ceremony wherein the king proved his continued virility

and physical ability to rule. Although there is great emphasis

upon the celebration of the jubilee in annals and autobiographies

of courtiers who served kings who celebrated the Sed, little is

known about the specific ceremonies.

By the reign of Hatshepsut (Dynasty 18), another ritual was introduced

that, like the Sed, emphasized the power of the king. This festival,

called Opet, was celebrated annually at Thebes. The ritual took

the form of a procession of the sacred barks of the Theban triad

(Amun, Mut and Khonsu) accompanied by the bark of the king himself.

Once within the sanctuary of the Luxor Temple, the ka (spirit)

of the king was rejuvenated for another year by its temporary

fusion with the gods.

«

previous

5 of 6

next

»

|

|

|

|

Figure

4: The gods Osiris (left) and Horus (right) (after Hobson

1987). »

| E

X P L O R E |

| The

Further Exploration page has many links to great

sites about Ancient

Egypt. |

|

|

|