The Montaigne Project

by Philippe Desan

Question: In addition to being the director of Montaigne Project you're the editor of the journal Montaigne Studies, and I want to find what is it about Montaigne that has captured and sustained your interest for these years.

Philippe Desan: Montaigne has been my major field of research for almost 15 years now. Montaigne is the equivalent of Shakespeare in the French culture. It is a name that is among the two or three best-known French authors, all times considered. I discovered Montaigne, of course, when I was in high school in France, but as a scholar it was about 15 or 17 years ago when I wrote my first book on the idea of method and I reread Montaigne very closely.

Philippe Desan: Montaigne has been my major field of research for almost 15 years now. Montaigne is the equivalent of Shakespeare in the French culture. It is a name that is among the two or three best-known French authors, all times considered. I discovered Montaigne, of course, when I was in high school in France, but as a scholar it was about 15 or 17 years ago when I wrote my first book on the idea of method and I reread Montaigne very closely.

Montaigne is the first person to write a book called Essais, the essays, and he defined the genre of the essay which is so popular today. Francis Bacon in the early seventeenth century writes a book of essays based on Montaigne, who had really been leading the entire field of a certain way of writing which was not really well defined. It seems to be going in many different directions. At the same time he's always asking the same questions: the motto of Montaigne is, "What do I know?" He is always asking the questions, I think, that define modernity.

Question: Let's turn to the Bordeaux copy, which is the focus of the Montaigne Project. What is the Bordeaux copy? What makes it special?

Desan: The Bordeaux copy has a very interesting status among French manuscripts. Montaigne wrote a single book in his entire life. He started writing in 1572 and he ended writing his essays the day he died, literally the day he died, in 1592. So he wrote the essays over 20 years and he published three versions of the book, always with the same title.

Philippe Desan interprets the notations on the title page of Montaigne's Essais. (Download: 1.19 MB)

Philippe Desan interprets the notations on the title page of Montaigne's Essais. (Download: 1.19 MB)What defines the Bordeaux copy? Four years before he died, Montaigne published what we call the 1588 edition of the essays. During the four years between 1588 and 1592, he added about 30 percent more text, making corrections in the margins of a copy of the 1588 edition he had with him; actually several copies. We know only one today because the other one that served for the production of the posthumous edition was destroyed during composition. So the Bordeaux copy is half manuscript and half book. It is a printed book of his own essays with about 30 or 35 percent of additions and manuscript corrections.

Question: So is it the only surviving copy of his essays that has his marginalia in it?

Desan: Yes. This is the only surviving document from the hand of Montaigne. Montaigne traveled to Italy and kept a travel journal that was lost in the eighteenth century -- it was printed in the eighteenth century but then lost. So yes, it is the only extensive document in his handwriting apart from some parliamentary acts and some letters--very few as a matter of fact.

Question: What is it that has allowed this copy to survive the years?

Philippe Desan shows Montaigne "going back in time" as he edits his Essais. (Download: 941 KB)

Philippe Desan shows Montaigne "going back in time" as he edits his Essais. (Download: 941 KB)Desan: Luck, pure luck. Preserving the Bordeaux copy is a novel in itself. In the introduction that I wrote for the publication of the Bordeaux copy, I tried to trace the history of the book. Montaigne's only surviving daughter inherited his library and for about 20 or 25 years the copy was probably kept in the tower where he wrote his essays. Then it was given to a convent in Bordeaux, and we don't really know what happened to it until the eighteenth century.

So we have about a century and a half where it was in a convent. A little before the revolution, somebody traveling from Paris--who actually became Minister of the Interior in France--discovered the manuscript, and at the time of the revolution all the convent libraries were seized by the new republic. Then we have a very strange story that is full of disappearances and reappearances. We know that the Bordeaux copy was in Paris in 1798 and then it disappeared for six years.

Nobody knew where it was. It resurfaced in the early nineteenth century, and since that time it has been well preserved and kept in Bordeaux. It belongs to the French Ministry of Culture, but it is deposited at the Bordeaux library where it has depended on the mayor of Bordeaux since the early nineteenth century. During this time, it has left Bordeaux only twice, for special showings in Paris.

Question: Now that we're in Bordeaux, let's talk about the Montaigne Project itself. What are the aims of the project?

The pages of the Bordeaux copy dispel a long-held myth about Montaigne. (Download: 1.24 MB)

The pages of the Bordeaux copy dispel a long-held myth about Montaigne. (Download: 1.24 MB)Desan: The aim of the Montaigne Project is to make accessible this manuscript that has really never been studied, in spite of what many people say. I can tell you that for over a century now this document, this treasure of the French culture--it is defined as such by the French government--has not been accessible. It can only be seen by very few people, mostly in darkness, handled with gloves--and not by the scholars themselves, but by approved special technicians sent by Paris.

When people pretend they have done editions of the Essais based on the Bordeaux copy, they probably glimpsed it a couple times or a few hours at most. But nobody has been able to do an edition on the Bordeaux copy because it has not been accessible.

There was a photographic reproduction, although a poor one, made in 1912 by the Hachette Publishing Company in Paris. Many people who say today that they have published an edition of the Essais based on the Bordeaux copy never went to see the Bordeaux copy, but based their work on this photographic reproduction in black and white, which is not that good. Imagine almost a century ago what the technology would enable us to do.

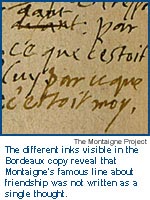

When I first studied the Bordeaux copy about 10 or 12 years ago I was struck by this idea that there are different inks used, and this tells us a lot more than we currently know about the composition of this manuscript. I wanted to create a color reproduction so that people could see the difference in inks.

A good example of this is the very famous sentence in which Montaigne defines friendship--it's one of the most beautiful definitions of friendship in French history. He writes of his friendship with his friend La Boétie, "Because it was him, because it was me."

If you have that in black and white, you take it as one single sentence. But if you see the reproduction in color, you discover that it had been written at two different times with two very different inks. Not only that, but by magnifying this portion of the manuscript you can see that the second part was written before the first part--"because it was me," was written before "because it was him." That kind of detective work is only possible with a color reproduction.

If you have that in black and white, you take it as one single sentence. But if you see the reproduction in color, you discover that it had been written at two different times with two very different inks. Not only that, but by magnifying this portion of the manuscript you can see that the second part was written before the first part--"because it was me," was written before "because it was him." That kind of detective work is only possible with a color reproduction.

Question: And that kind of detective work will be made possible by the project because in addition to creating a book you're creating a DVD?

Desan: Exactly. The most interesting part for me is not so much the book reproduction, which will be fairly expensive and mainly for collectors and libraries, but probably not for junior faculty or junior scholars.

The Montaigne Project allows scholars to read passages that Montaigne crossed out. (Download: 1.12 MB)

The Montaigne Project allows scholars to read passages that Montaigne crossed out. (Download: 1.12 MB)We will produce a version on a DVD which allows you to blow up the letters themselves five, six, eight times so you will see on your screen a portion of the line about that high. That will really allow us to do tremendous types of work using systems like Photoshop, for example, or other software that allows us to play with contrasts and magnify the text, which you cannot do when you see a document, even printed in very good condition by a very good typesetter or printer.

Question: You couldn't take the Bordeaux copy, lay it on a scanner and capture each page. What were some of the technical and logistical hurdles that you had to overcome to create the book?

Desan: It took three years to go over the hurdles. First of all there were the political ones, which were probably the most difficult. At the time, the French minister of culture was a socialist. She was the one who was supposed to give the approval because the Bordeaux copy is a treasure of the French culture. But this book is deposited in the city of Bordeaux, and the mayor of Bordeaux is the previous prime minister of France under the right government.

We had a lot of tension because I needed to have two permissions at the same time in order to proceed. Then, of course, we had tremendous trouble finding a photographer who was designated by the French government, and we had to work in almost total darkness, without using a flash, within what we call in French a chambre forte--a safe. We had to design a special camera, actually a special chamber, with a lens that was specially built. Three times the French government sent someone to Bordeaux to verify that we were not using more lumen than what we were allowed to. They would not allow light to be on the copy itself.

Very few people were allowed to handle the book at the library of Bordeaux. They had four or five people total and they were the only ones able to touch the book. We photographed all the rectos before the book was turned over and then did all the versos, which is of course a huge problem in finding an equilibrium between the light because we have to produce the pages--recto and verso--together.

It is a very costly operation. It could not have been done by the French government, which did not want to invest in it. It was done only by finding a donor who was willing to subsidize the entire project.

Question: In addition to there being rivalries between the Bordeaux government and the French national government, are there any rivalries between scholars of the Bordeaux copy and scholars of the Paris copy?

Desan: They are more than rivalries. There's a real war basically since the nineteenth century because the Bordeaux copy is really the pride of the Bordeaux region. This is the only written document we have in the hand of Montaigne.

Differences in the handwriting show Montaigne composing in some places and copying from another text in others. (Download: 1.06 MB)

Differences in the handwriting show Montaigne composing in some places and copying from another text in others. (Download: 1.06 MB)As I said before, when Montaigne died there were actually two copies. It's like making copies on a diskette of your work today--you don't want to lose it. Montaigne had the same problem in the sixteenth century: he had two copies of what we call the 1588 edition of the Essais annotated in his own hand. The one that was sent to his daughter of alliance Marie de Gournay in Paris is not the Bordeaux copy. It's something else that was used to produce the 1595 edition, and was subsequently destroyed by the printer in the process of creating that edition.

These two texts, by the way, are not identical, but not that much different. When scholars say, "Oh, there's huge differences," it's not true at all. The differences are less than 2 percent, probably, but they do have some significant differences. The copy that was sent to Paris served in the production of the first posthumous edition, the 1595 edition, but was accepted widely in the seventeenth, eighteenth and part of the nineteenth century. What I call the battle for the Bordeaux copy was really won in the early twentieth century only when the Bordeaux copy--because it is the interesting and incredible document that we have today--served to produce all the editions.

The problem with the Bordeaux copy is that it is not complete. It was bound probably in the seventeenth century and the binder at the time didn't pay much attention to what he was doing and cut about a quarter-inch all around the book itself. So on some pages, sometimes two lines of manuscript additions were lost. You could not do an edition today of the essays of Montaigne from the Bordeaux copy alone because you would not have all the text, so you need to go to the 1595 edition. That makes the problem interesting for many scholars, and the battle continues today between these two copies.

Question: Now that the work of photographing the Bordeaux copy is complete, what happens to the book itself?

Desan: The Bordeaux copy itself is going to rest in total darkness for the next 50 or 100 years. The quality of the inks is slowly but surely disappearing. You can see when you compare what we have now to the 1912 black-and-white photographic reproduction that the inks have gotten lighter, and the French government decided this is it. The purpose of the reproduction of the Bordeaux copy is basically to preserve the physical document as we have it.

Question: Did years of close contact with the Bordeaux copy open up any new insights for you about Montaigne--things you hadn't thought about before? Things you hadn't noticed about Montaigne's work before?

Desan: Yes, certainly, because you really see somebody at work. No printed reproduction can convey what you have in the Bordeaux copy. You can see the way Montaigne crosses a line, a thin line when he gets upset. You know that very well: When you write you can cross something out three times with a big cross, or you can write in small letters. You can see Montaigne copying from another copy, and sometimes having a much larger handwriting. You can really see the changes being made, and you can see the process of writing the Essais in the Bordeaux copy that no printed text can show you.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR |

Philippe Desan

Philippe Desan is Howard L. Willett Professor in the Department of Romance Languages at the University of Chicago. He is the editor of the journal Montaigne Studies and is currently working on a Montaigne Dictionary. Desan's research focuses on sixteenth-century French literature, particularly Montaigne and La Pléiade, as well as the interplay of literature with politics, philosophy and economics in the Renaissance. His most recent books include L'Imaginaire économique de la Renaissance (Paris: Presses de l'Université de Paris-Sorbonne, 2002) and Montaigne dans tous ses états (Paris-Fasano: Presses de l'Université de Paris-Sorbonne & Schena Editore, 2001). Desan received his Ph.D. from the University of California at Davis.

COPYRIGHT | This article is based on an interview conducted November 9, 2001. Copyright 2002 the University of Chicago.