So let me tell you about the Swift Gamma-Ray Burst Explorer Mission. It’s helping with the problem of detecting and locating gamma-ray sources so that we can study them.

Gamma-ray bursts are very luminous explosions. They’re like having a lighthouse blink at us from the farthest reaches of space. The problem is they’re highly energetic but very brief – they only last a few seconds to a few minutes. Unless you have a wide-field telescope like a coded aperture, you will miss it.

An artist's concept of the Swift Gamma-Ray Burst Explorer catching a gamma-ray burst.

Credit: NASA

The scientific objectives of the Swift mission are to determine the origin of gamma-ray bursts and to use these to understand the early Universe. And what we’ve learned is that gamma-ray bursts, even though they’re really bright and you’d think that they’re occurring just next door to the solar system, they’re actually in distant galaxies, and they’re tremendously energetic explosions. Most occur when massive stars run out of nuclear fuel and the core of the star collapses into a black hole or neutron star. When this happens, gas jets punch through the star and blast into space and heat up the gas around it, and this generates the short-lived afterglows in other wavelengths. What we’re doing with Swift is to use those really bright flashes of gamma-rays to study what galaxies and stars were like in the early Universe.

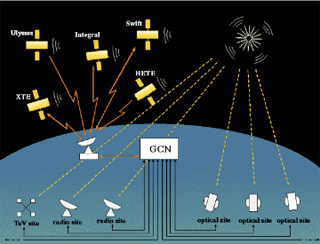

Schematic of the GRB Coordinates Network (GCN), a system that distributes information about the location of a gamma-ray burst (GRB). The spacecraft sends the GRB location information down to a ground station, which in turn relays it to the GCN at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

Credit: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center

This is how it works. Swift has an instrument called the Burst Alert Telescope (BAT). When the BAT detects a gamma-ray burst that’s significantly above the background rate, it triggers a burst detection. In about 10 seconds it can calculate the location of the burst. This means Swift is fast enough to actually catch a GRB in the act.

Then a computer on board Swift immediately transmits the location and the burst’s intensity to the world through the GRB Coordinates Network (GCN) so that ground-based telescopes can search that area of the sky for the afterglow – the energy from the GRB as it fades to longer wavelengths like X-rays and visible light. Analyzing afterglow spectra is how we determine the composition of and distance to the GRB. So when a burst happens – and they happen several times a month – imagine that people all over the world are getting paged and called and instant-messaged and emailed all at the same time with news of this event way out in space.

Swift has two other instruments on board, the X-ray Telescope (XRT) and the Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope (UVOT). These are just normal focusing narrow-field telescopes. When we detect a gamma-ray burst, Swift immediately slews and points these instruments at the direction of the burst so we can look at it in the X-ray and optical wavelengths. These instruments complement each other – the BAT uses coded aperture imaging to look over a wide field of the sky and the XRT and UVOT have narrow fields of view for a more detailed look at the area of the GRB.