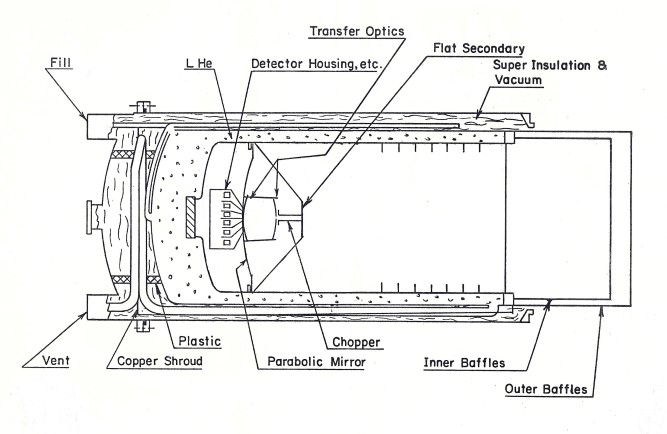

A lot of trial and error is involved when you design something that has never been built before. To be sufficiently cooled our telescopes were surrounded by a layer of liquid helium in a cylindrical vacuum vessel with several layers of insulation. The vacuum vessel, called a dewar, shielded the telescope from any air or water that would otherwise condense on it. We also had to build detectors that were sufficiently sensitive for the scientific aims of the observations. A drawing of the telescopes our Cornell group launched is shown below. Once built, they were fitted into rockets that would be subjected to violent shaking on launch. We worried that these vibrations would break the dewar’s vacuum, causing the helium to explosively evaporate. Launch aboard our small rockets was far more violent than the launches experienced by astronauts going to space. The rockets astronauts ride are deliberately built to minimize shaking.

Dewar: Drawing of a liquid helium (LHe) cooled telescope. Light enters the telescope from the right and is focused by the parabolic mirror at left onto detectors at center. Liquid helium at 4 degrees centigrade above absolute zero surrounds the optical components, and is itself enclosed in, and insulated by, a vacuum layer to keep it cold. Baffles restrict stray light from interfering with observations.

Credit: courtesy Martin Harwit

Our rockets could only get about five minutes’ worth of observing time above the atmosphere before falling back; but because the detectors launched in these telescopes were so sensitive, even that short a time gave us our first view of the universe and its emissions at long infrared wavelengths. We were able to start figuring out what added technologies we would need to develop for further progress. The program we were pursuing attempted to solve the problem of making the whole spectral range in the infrared available for astronomical observations.

At the time, many astronomers considered the cost of the rocket program too high and thought that everything could be done from the ground much more cheaply. Indeed, our rocket observations were initially costing more and returning less scientific information than ground-based observations. We knew it would take time, persistence and patience to change this!