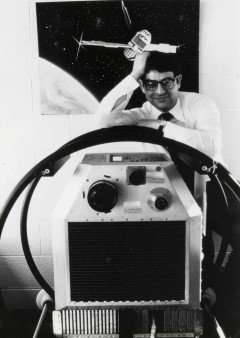

Giacconi and Uhuru: Riccardo Giacconi stands with the Uhuru satellite, circa 1970.

Credit: Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

If the hope of being able to develop the X-ray telescope sustained us in the beginning, the certainty of being able to do great astrophysics with relatively simple instruments provided an enormous stimulus to continue. In 1963, Herbert Gursky and I submitted a plan for X-ray astronomy to NASA that outlined a program from rocket experiments, to a dedicated satellite, to imaging X-ray telescopes, and finally, to a 1.2 meter X-ray telescope. This plan was based on a sober consideration of scientific requirements, though quite bold in approach. Our program also was to be completed in times that were hopelessly optimistic.

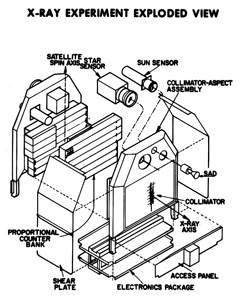

For the satellite mission, I conceived of an extremely simple and reliable experiment whose data should be easy to interpret. The detector on the satellite consisted of two proportional counters with apertures of 0.5 x 5 degrees and 5 x 5 degrees. As the satellite rotated slowly on its axis, the detector would sweep a five-degree-wide band around the sky. The speed of the rotation, as well as pointing, could be controlled from the ground. Star sensors permitted us to locate the source of X-ray emission in the sky. We arranged with NASA to send us a portion of the data through a telephone line each day. The satellite was launched in 1970 from the San Marco platform in Kenya on the Kenyan freedom day and was named Uhuru, which means freedom in Swahili.