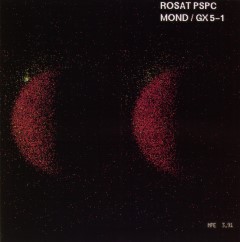

X-ray Moon and X-ray Star: This image of the Moon in X-rays was made in 1991 using data from the Roentgen Satellite (ROSAT), an X-ray observatory. In this picture, pixel brightness corresponds to X-ray intensity. The Moon reflects lower energy X-rays (shown as red) from the Sun. The source of high energy X-rays (shown as yellow) is a distant binary star system. The background is speckled with X-rays from many distant, powerful active galaxies. The picture also shows the Moon passing in front of of and obscuring the binary star, a phenomenon called occultation.

Credit: ROSAT, Max-Planck-Instituts für extraterrestrische Physik, NASA

On June 18, 1962, the AS&E team launched an Aerobee rocket from White Sands, New Mexico. Its payload was three Geiger counters. The flight, which only lasted a few minutes, was intended to detect X-rays coming from the Moon. Instead, the Geiger counters detected a dim, uniform glow across the sky and one brilliant source in the constellation Scorpius. The X-ray detectors also found a possible second X-ray source in the general direction of Cygnus and Cassiopeia. The team at AS&E published their results at the end of the year. The X-ray source was a binary star system designated Scorpius X-1. Sco X-1 was the first cosmic X-ray source discovered, and, aside from the Sun, it is the strongest source of X-rays in the sky. Then in the spring of 1963, we flew a new NRL-developed X-ray detector system that confirmed these results and more. Our detector showed clearly Sco X-1 as the strong source of emission and we gave its position more accurately (about half a degree) than the AS&E experiment. Another source we found was the Crab Nebula.

We continued our experiments as part of an ongoing effort to map these sources, using rockets carrying Geiger counters to measure X-ray emission. These instruments swept across the sky as the rockets rotated, producing a map of closely spaced scans. As a result of these surveys, eight new sources of cosmic X-rays were discovered, including Cygnus X-1, which we were able to confirm as the possible second source in the AS&E rocket flight. By 1965 we had a catalogue of 30 sources, but we had reached the point where it was obvious that you couldn't fire enough rockets to give you an adequate enlargement of the X-ray catalogue. It would take too long to do it that way. Although rockets paved the way for X-ray astronomy, a satellite’s ability to stay above the atmosphere for years, instead of minutes, would allow the counters to measure and record vastly more data about X-ray sources.