Copernicus Satellite in the Clean Room: This is the Copernicus satellite that is the frame for the telescope in the integration facility at the Goddard Space Flight Center. The spacecraft will eventually hold the telescope and all of the systems required to run the observatory including the pointing and tracking systems. Because all of the components are so small, they must be tested and assembled in a clean room to prevent dust from interfering with the moving parts, or blocking the slit of the telescope where the light from space will eventually enter the telescope.

Credit: Image courtesy Ed Jenkins

My thesis advisor at UC was Bob Odell who was chairman of the department and who would later become the project scientist for the Hubble Space Telescope. I finished the degree in 3.5 years and then got my dream job at Princeton University with my dream mentor, Lyman Spitzer. Among other research areas, Lyman was a pioneer in the interpretation in the observation of interstellar gases and wrote many theoretical and observational papers on the nature of the gas and dust between the stars.

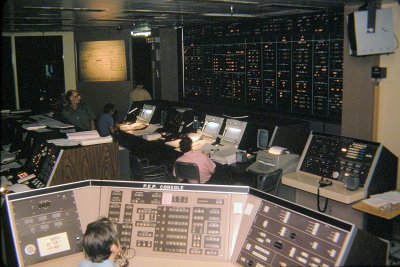

For 12 years I worked on the Copernicus satellite which was opening up a new waveband, the ultraviolet, to real quantitative measurements of interstellar gas and dust between the stars. Ultimately the discoveries relate to how stars are formed. Copernicus was launched in 1972, midway between the creation of NASA and the launch of the Hubble Space Telescope. It was an important waystation on the way to building the Hubble Space Telescope and other Great Observatories.

Eventually the satellite was turned off; I was young and did not understand why you would turn off something that was working. I eventually understood that there is a fixed budget and if you want to have new projects then you have to close down old projects.

This period of time was a turning point in astronomy: between photographic detectors and electronic detectors, and between toy computers and real computers.

By the time Copernicus was closed down, another major change in astronomy was in the offing, namely a rebirth in the importance of optical astronomy. Through a long and complicated, though not unusual set of events, I now found myself in optical astronomy.

The history of optical astronomy is intimately tied to the general evolution of technology. In many ways the development of the technology for space astronomy, as I would soon learn, led to major improvements in ground-based instruments, many of which were implemented in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey.