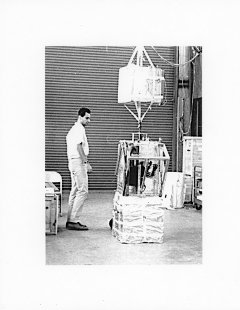

Far IR Sky Survey: Nick Woolf with the gondola, holding the telescope for the sky survey. The gondola would be taken above the atmosphere with a balloon.

Credit: Image courtesy of Nick Woolf

We sat around thinking, well this means observing in the infrared. Then the question arose, “have any of you had any experience in the infrared?” It was even worse than that – it needed the most sensitive infrared detector available! And very few astronomers had made infrared observations at that time, or knew the difficulties of working in the infrared. I said, “Well, there was a graduate student in the optics group while I was in Manchester. He had the office next to mine, and he worked in the infrared.” That was the closest anyone was to infrared work, so I got the job and I became an early infrared astronomer.

My interest in optics had led me to working in new wavebands and on new problems. We went on to make ground-breaking observations of Mars, and I moved on to other observations with Stratoscope II. We made discoveries such as the absence of water ice in interstellar dust (scientists thought at the time that interstellar dust was mostly made up of water ice), and the presence of huge amounts of water vapor in the outer layers of cool, giant stars.

Later at the University of Minnesota, I observed the interstellar dust in the infrared, and found that it was actually made up of silicates. Silicates, which were previously thought to be known only here on Earth, were suddenly ubiquitous, and here they were coming out of stars, forming into interstellar clouds and being available for the formation of planetary systems and also being seen in comet tails. This work was a development with the same detector that was used in the Stratoscope II flights.

I have already mentioned that while I was at Lick Observatory in the early 60s, I was working on interstellar lines. While at Princeton I also interacted with Bob Dicke in the physics department in addition to the astronomers. Bob had predicted that there would be microwave radiation filling the Universe. He asked me about detecting it and I mentioned the interstellar molecules (meaning cyanogen), which are driven to rotate by the radiation falling on them. But he didn’t follow up on my comment, and I, fearing that I had said something silly, shut up. If I had explained further, Bob would probably have won a Nobel Prize. As it was, we only returned to the cyanogen a year later after Penzias and Wilson had found the microwave background radiation with a radio telescope.

I will never regret speaking to Martin Schwarzschild, but I do regret not continuing that talk with Bob Dicke. The moral of that story is that just because you are ignorant does not mean you should be quiet. Most of the important things discovered have been by people who didn’t understand what was going on but weren’t quiet about it. My friend Wal Sargent discovered helium 3 in a star as a result of not being silent and not really quite understanding what he was doing, but thinking that he’d at least seen something rather important and that he should try to understand it.