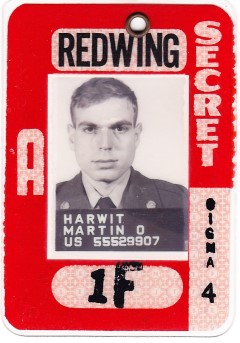

Martin Harwit's Clearance Badge: Security required soldiers to wear clearance badges at Eniwetok and Bikini at all times.

Credit: Photo Courtesy Martin Harwit

The Army stationed me in a research laboratory that dealt with atomic and hydrogen bombs, and with fall-out of radioactive debris. In the spring and summer of 1956, I was sent to the Pacific Proving Grounds, as part of an operation code-named Redwing. The purpose of our activities was to test a series of bomb designs at two atolls, two small rings of islands in the Marshall Islands, far from anywhere else in the vast Pacific Ocean. One was Eniwetok Atoll, where I spent most of my time. The other was Bikini Atoll, where a small group of us often worked for several days emplacing neutron dosimeters in advance of planned hydrogen bomb tests. Later we’d collect the dosimeters for laboratory analyses of the neutron flux the bombs had generated.

Redwing included the first airdrop of a US hydrogen bomb. It exploded at 5:51 am, local time, May 20, 1956, at an altitude of 10,000ft. For safety we were thirty miles away out at sea. It was still dark that morning as a blinding fireball instantly turned darkness to daylight to a distance of several hundred miles. Shooting upward the fireball turned into a roiling mushroom cloud that raced to a height of 25 miles before spreading to cover what appeared to be the entire sky, eventually to a width of a hundred miles. All of this evolved in ghastly silence, in what seemed forever before a loud crack jarred us out of the horror we had just witnessed. The explosion’s sound wave had taken two minutes to reach us. The neutron counters we had earlier emplaced strategically conveyed little information; the bomb had missed its target by five miles.

Fireball: Fireball from the first airdropped US hydrogen bomb.

Credit: Photo courtesy of National Nuclear Security Administration / Nevada Site Office

Had this bomb been dropped over any large city it would have instantly killed several million people. Other millions would have perished agonizingly from radiation exposure. Fortunately, most world leaders today recognize that bombs like these should never be used in war.