In May 1609, Galileo had heard about a tool using lenses that could make far things appear close. He immediately made one of his own out of a tube and two lenses. His telescope was a big hit in Padua and Venice, and the Paduan Senate gave him 1000 florins per year and a professorship for the invention, which could be used by the military as a spyglass.

In March of 1610, only ten months after he first heard about the telescope, Galileo published a book which described the celestial observations he made with his telescope. It was titled The Starry Messenger, Sidereus nuncius in Latin.

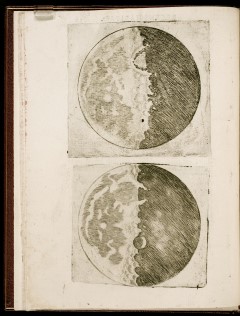

Illustration of the Moon’s Craters from Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius: Galileo Galilei published Sidereus nuncius, Starry Messenger, in 1610. The treatise included observations Galileo made with his telescope. These depictions emphasize his realization that walls of deep craters on the Moon cast shadows. He thereby realized that the entire surface of the Moon was pitted with craters and mountains. He would not have been able to reach this conclusion without the aid of a telescope.

Credit: Galilei, Galileo. Sidereus nuncius. Venice, Thomam Baglionum, 1610. Rare Books Collection, apf6-01298, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

The book included descriptions of mountains and craters Galileo saw on the Moon. He looked at the Milky Way and saw that the milky appearance was actually due to myriad separate stars that could not be resolved by the human eye. Galileo also described four moons he discovered orbiting around Jupiter and reported the fact that Venus showed phases, an observation that revolutionized and finally ended the discussion about an Earth-centered Universe. All of these things were complete surprises. The book was a best seller.

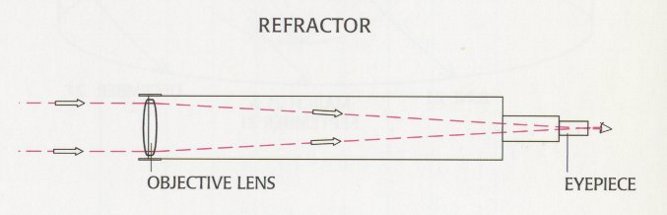

These telescopes, known as refractors, were made with larger and better lenses over time, but there were two problems that just wouldn’t go away. First, imperfections in the lens could make images appear fuzzy, like looking at an object at the bottom of a pool. Second, bands of color, like a rainbow, appeared at the edges of an image made by a telescope. No matter how big the telescope got or how well the lens was made, these bands of color always appeared and distorted the images. The problem was known as chromatic aberration.