Astronomy frequently progresses in the following way: a scientist has questions. A theorist can then create computer models that explain the existing data based on a question. However, the model also makes predictions which scientists cannot currently test because the telescopes aren’t powerful enough, or for other reasons. In response, a telescope is built that can actually make the measurements needed to confirm the model. The measurements often turn out to be different than what was predicted by the theorist. Scientists then have to scramble to explain the differences. After a few years of work, a scientist will then say, “I can explain what we observed and make these other predictions that I can’t test.” So, there’s a constant swishing back and forth between theory and observation: theory gets ahead of observations because the observing comes in concrete chunks, then a new telescope that is better than the past telescopes or a new instrument on an existing telescope, such as a camera or detector, provides new data. Frequently, the new data is a surprise and the cycle begins again.

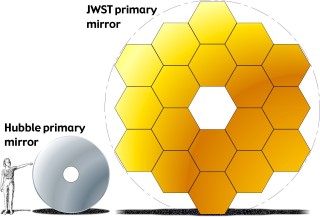

This concept of ebb and flow of understanding and the need to have new telescopes moving forward has an interesting consequence in practice. Usually there is no need to build a new telescope that is a copy of a previous design. New telescopes need to be of a different design to test new ideas as we have discussed. Better technology and bigger telescopes are required. Usually, this implies long delays in actually achieving the launch of a new telescope. The James Webb Space Telescope, for instance, is an infrared telescope that is a natural consequence of many small telescopes that have gone before. From the time it was chosen as a national priority to the time of its expected first light will be about 20 years. That is a long time to wait. Some of the many motivational ideas will have gone out of date, but new things will be discovered and we will move forward.