We were able to interest NASA and the Air Force in funding an X-ray experiment, so, in 1960, we placed a small-aperture Geiger counter on a rocket to search for X-ray stars and lunar X-rays. Unfortunately, the flight failed when the rocket misfired. By the next year we had improved upon our experiment and prepared it to be launched again. We now had a more sensitive instrument that also had a large field of view, which increased the probability of both observing a X-ray source anywhere in the sky and receiving a sufficient number of photons to make detection of them statistically significant. In effect, the payload we designed and flew was 100 times more sensitive than any flown until then. But this attempt also failed when the door to the detector failed to open.

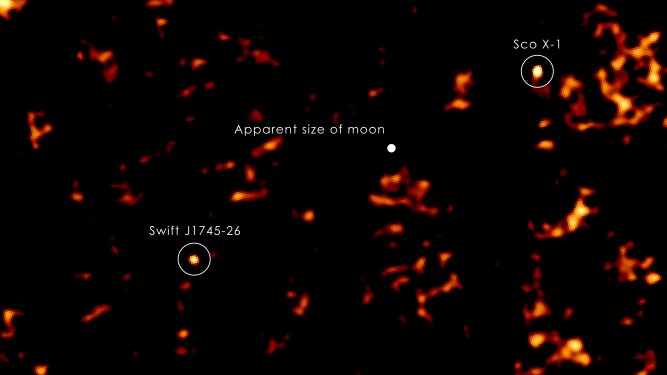

When our experiment finally launched on June 18, 1962, data revealed a very strong peak of radiation in the south. The source of this radiation did not appear when our optical photometer was pointed at the Moon, but, it did appear in our X-ray detector when we were pointing away from the Moon. After weeks of analysis, we concluded that the most likely source of the observed radiation was from outside the solar system, and that the strong peak was from the general direction of the Galactic center. The source was a double star system named Scorpius X-1 (Sco X-1 for short).

The discovery was beyond all we had hoped to find! Here was an object that emitted a thousand times more X-rays than the Sun, and a thousand times more energy in X-rays than in visible light! Clearly we were dealing with a new class of stellar objects in which physical processes not known in the laboratory were taking place. Soon after the announcement, the NRL group, led by Herbert Friedman, used a larger area detector with better angular resolution than the AS&E instrument to confirm our discovery of Sco X-1, as well as to observe the Crab Nebula.