The instruments we were using were really, really simple. Frank had a technician-engineer, Arnold Davidson, who made detectors. Frank’s company made dewars, which are the bottles that hold the ultra-cold liquid gases that cool those detectors. He was actually very proud of inventing an all-metal liquid helium dewar, which was important because helium dewars before then were all glass, and you had to be really careful. With the metal one, you could put it in the back of a truck and carry it up to the mountain without worrying too much about breaking it.

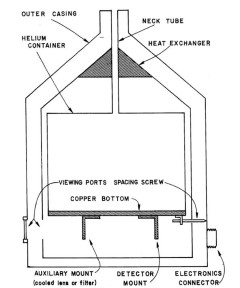

Metal Dewar: Diagram of metal dewar used by Frank Low and his student Douglas Kleinmann on the Catalina Observatory 28-inch telescope to make many early discoveries in the mid-infrared. This image is from Douglas Kleinmann's Rice University Ph. D. Thesis.

Credit: Courtesy Douglas Kleinmann and the Rice Digital Scholarship Archive

A dewar is really pretty much a thermos flask. You put liquid helium or liquid nitrogen into this container, and you have to insulate it really well to keep the liquid from rapidly boiling away. Like in a glass thermos, the best way to insulate is to surround the liquid with a vacuum jacket, so you have to have a case that keeps the air out. You pump the air out of that and you get a vacuum that heat can't easily penetrate. In fact, I had spent some summers at Argonne National Laboratory working with liquid helium held in a glass dewar that somebody had spent hours making in the glass-blowing shop. It was about three feet high and so delicate I was not allowed to touch it. If you put a glass dewar in a truck to carry it somewhere, it was bound to break. Frank’s development was to learn how to make this out of metal so that you could put them on telescopes, you could launch them in rockets, put them on balloon payloads, and so on.

I would cart myself up to the telescope and observe probably six nights a month. Then in the time in between, I would drag myself down to Tucson and fix the equipment, reduce the data, and write papers. It was hard work.