We can’t predict what the next discovery will be; if it’s predictable, it’s not a discovery. However, I’m sure we will image more planet systems, for example. Each one of those will seem like a discovery, but after a while, the science will end up being more about fleshing out the diversity of planetary systems, and less about discovering new planets.

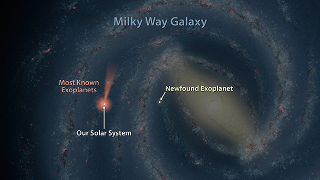

Exoplanets in the Milky Way Galaxy: Astronomers have discovered one of the most distant planets known, a gas giant about 13,000 light-years from Earth. The planet was discovered using a technique called microlensing, and the help of NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope and the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment, or OGLE. In this artist's illustration, planets discovered with microlensing are shown in yellow. The farthest lies towards the center of our Galaxy, which itself is 25,000 light-years away. Most of the known exoplanets, numbering in the thousands, have been discovered by NASA's Kepler Space Telescope, which uses a different strategy called the transit method. Kepler's cone-shaped field of view is shown in pink/orange. Ground-based telescopes, which use the transit and other planet-hunting methods, have discovered many exoplanets close to home, as shown by the pink/orange circle around the Sun.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

It’s our dirty little secret as scientists that we’re not smart enough to plan out making these big discoveries; we’re just smart enough to recognize them when we trip over them. Often in science, certainly in physics labs, people sometimes notice something funny about their equipment but they just go on until finally somebody says no, I don’t understand that. I’m sure there are people who ruined their careers by asking too many questions about things they didn't understand and getting lost in trying to find answers.

But once in a while it’s worth a Nobel Prize. There are stories of people who looked into something that had been a nuisance for other investigators and it turned out to be really important. There’s something called the Mössbauer Effect, which has to do with absorption of gamma rays in crystals. Mössbauer got a Nobel Prize for it, but it turned out lots of people had seen it before; they just didn’t recognize it as anything other than an experiment that did not work the way it was expected.

I think a really good scientist has to have a good sense of when to follow something up and when to just dismiss it as something that is not important and you ought to move on. That’s something you only develop after maybe making a lot of wrong choices.