What changed between 1929 and the 1960s? I puzzled over that because the assumption always is that new technology drives new science. I thought, maybe the answer is in radio astronomy. Before radio astronomy came along, all astronomers knew to study was stars and emitters of visible light. Radio astronomy demonstrated that there are really interesting things out there that you can’t even see in visible light. That would open the field to the use of other wavelength regions. So radio astronomy really broke the paradigm that astronomy was all about visible light.

But there is another angle. Even if it’s really exciting to be a pioneer in a field of astronomy, if there’s nobody else to talk to, nobody that appreciates what you’re doing, you don’t get to exchange ideas. That's the situation Petit and Nicholson were in. I think a key to the flowering of infrared astronomy in the 1960s was the groups I just mentioned that provided a forum for technical discourse and an audience to appreciate what you were doing. A demonstration is that a Russian astronomer started out in infrared astronomy in the 1960’s also, but no other Russians got interested and he dropped out and took up planetary exploration. The same sort of thing happened in radio astronomy. It took twenty years from the first observations by Karl Jansky for the field to get started, and then it flourished with many people participating.

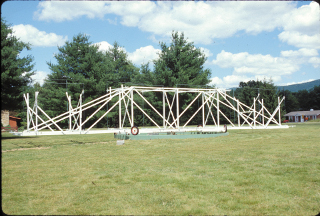

Replica of the Janksy Telescope: Replica of the antenna used by Karl G. Jansky to discover the radio Universe. Affectionately known as “Jansky’s Merry-go-Round,” this antenna’s turntable allowed Jansky to learn the direction of any signal he picked up. It was part of a program by Bell Laboratotries to locate sources of 20.5 MHz radio signals that might interfere with their overseas wireless communications. He located thunderstorms and the famous hiss that he determined came from the center of our Milky Way Galaxy. The discovery was widely publicized, appearing in the New York Times of May 5, 1933. Grote Reber, another pioneer of radio astronomy, suggested that this replica be built in Green Bank to exact specification, down to sourcing old Model T tires for the rotation axis.

Credit: NRAO

Another key to the flowering of infrared astronomy was money. Nancy Roman, who led astronomy at NASA headquarters, had a big role in establishing NASA in space science. Nancy funded many of the infrared groups when other astronomers or astronomy departments would not. Frank Low got some of his money a different way. It was from Air Force Cambridge Research Lab that was worried about sending heat seeking missiles up at incoming Soviet warheads and instead locking in on an infrared star. They wanted the sky mapped for bright infrared sources. These were unconventional but rich funding sources. Nancy played a huge role, and a very much under-appreciated role, in funding this weird stuff that was going on outside of astronomy departments.

If you fold in the fact that, for some reason I haven’t really figured out, astronomers were kind of hostile to radio, X-ray, infrared-- all these new fields-- when they first started up, I think it explains a lot about what it takes to make a new field really start to go. I think it’s probably broader than astronomy, but we have a good example there. You had a science that was very centered on one spectral region and set of techniques. It’s doing very well with those techniques, it has all its rules of engagement, understands the limitations of the techniques and so on. Then a bunch of people who are not licensed in that field come along with a brand new way of doing things, and people are not always as receptive as in hindsight as you think they should have been. Eventually as the worth of the field becomes obvious and tools are developed that are more familiar to everyone, the new initiative can take root.

When I first saw this picture, it was disappointing. I had been taught that science was led by logic and crisp decisions that led directly to progress. Now, however, I feel better. It is comforting to realize that science is a very human endeavor, and many of the human complexities we see in other areas affect science also.